During winter, when the sun angle is low, we frequently lack sufficient surface heating to warm the atmosphere and develop a deep layer in which turbulence can mix the near-surface air with the atmosphere aloft. The layer in which that turbulence occurs, which is known as the boundary layer (or mixed layer), can be very shallow. As a result, emissions from our urban area are trapped in the valley, leading to elevated particular matter concentrations.

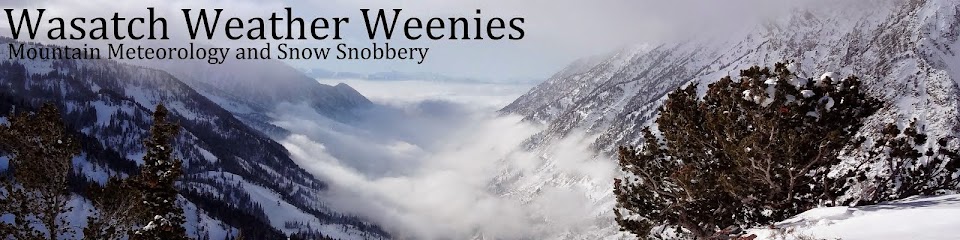

An example is the inversion event of late December 2016. As can be seen in the photo below, taken on the afternoon of 30 December, smog is confined primarily to the valley and the visibility improves dramatically with altitude. Typically in these instances, one can find clean air simply by going to the mountains.

A sounding taken that afternoon at the Salt Lake Airport is very typical of of wintertime pollution events and features a very shallow boundary layer that extends from the surface to about 850 mb, which equates to about 300 meters (1000 feet) of depth, roughly consistent with the depth of smog above. At the top of the boundary layer is a strong inversion in which the temperature increases very dramatically with height nearly 15ºC from about 850 to 800 mb (about 500 meters).

That inversion essentially puts a lid on the valley atmosphere. In the winter, we have met the enemy and it is us. We can't really blame our pollution problems on anybody else.

In the summer, the situation is much different. The sun angle is high and there is strong heating of the surface and lower atmosphere, which leads to a deep boundary layer and turbulent mixing. In contrast to winter, when the pollution is confined to near the valley floor, it can be much deeper. For example, the photo below from Snowbird's Hidden Peak cam was taken yesterday. Smoke and pollution extend to and above mountaintop levels and the Oquirrh Mountains to the west are obscured.

|

| Source: Snowbird |

From about 850 mb to 750 mb, the temperature decreases at about 1˚C per 100 meters. Such a layer is known as dry adiabatic and the air density in such a layer is constant with height. Turbulence has little trouble mixing through such an atmosphere and this is why we see smoke, haze, and pollution through such a deep layer.

There is a very weak stable layer at about 750 mb that might cap the turbulence, however I suspect at times strong thermals penetrated to greater heights than that. The paragliders will know.

So, unlike wintertime pollution episodes, during the summer, we have mixing through deep layer.

Another difference is the pollution sources. Long-range transport plays a role in the summer. Yesterday afternoon's MODIS image shows several major fires over the western U.S. Smoke and trace gases from those fires are being transported into our area. There is probably no single fire that is producing our smoke. Some of it is long-range transport from California, Oregon, and possibly Idaho, and some might be coming from the Goose Creek Fire along the Utah-Nevada border. There are some smaller fires in the vicinity that might serve as local sources in some areas.

|

| Source: NASA |

Over the last five days, PM2.5 at Hawthorne elementary has been on the boundary between good and moderate levels. This is somewhat higher than we would expect this time of year in the absence of smoke. Ozone shows a stronger diurnal cycle, poking up into moderate values on some afternoons, occasionally approaching the cusp of unhealthy for sensitive groups.

In a situation like this, the mountains do not necessarily provide a reprieve from the pollution. It is even possible in the afternoon that ozone is higher than in the valley (this reflects transport and air chemistry that I don't have time to get into today). In patterns like this, I typically exercise in the morning when ozone concentrations are typically lower.