I get a lot of questions about climate change that don't have a simple answer. As the saying goes, the devil is in the details and the answers to climate change questions are not easily generalized.

Perhaps the hardest are those pertaining to the effects of climate change on avalanches. There are many ways that weather, snowpack, and terrain affect snowpack and there are many types of avalanches. Climate variables that affect avalanches include temperature, cloud cover (and its effects on solar and long-wave radiation), humidity, wind, precipitation type (rain or snow), precipitation intensity, and precipitation frequency. The influence of each of these can vary with elevation and aspect. Beyond the effects of greenhouse gases on climate, dust and black carbon due to land-surface disturbance or fossil fuel combustion can have a strong impact on the snow. Finally, avalanches need a natural or human trigger and, when it comes to the latter, homo sapiens are not exactly a rational or predictable species.

This will be a two-part post on climate change and avalanches, beginning here with an overview of climate change in mountainous regions. As is well documented, we are experiencing a shift to warmer temperatures. For example, below is the departure of the annually averaged temperature from the 20th century average for the western continental United States from the Rocky Mountains westward. The last year with a temperature below that average in this region was 1993. Since 1993, 9 years have been more than 2˚C warmer than that average. Prior to 1993, only one year eclipsed that level of warmth. We no longer live in the climate of the 20th century.

|

| Data Source: National Centers for Environmental Information |

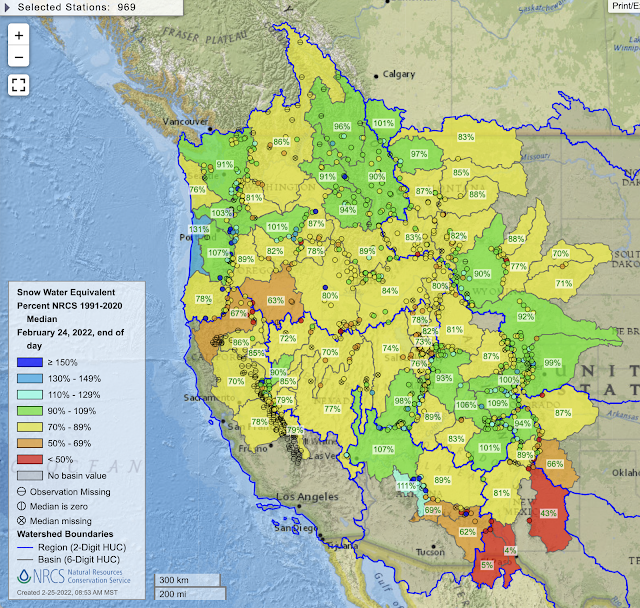

Other long-term trends that have been detected in many mountainous regions include an increasing frequency and severity of warm waves, a decrease in the fraction of cool-season precipitation that falls as snow, more frequent mid-season snow ablation events (i.e., snow loss due to melting or sublimation), and a decrease in the amount of wintertime precipitation retained in the snowpack at the end of the snow accumulation season. In some cases, especially for snow-related variables, these trends are elevation dependent. For example, decreases in the fraction of cool-season precipitation that falls as snow are largest at lower elevations and may be non-existent at upper elevations where it can be much colder and a few degrees of warming is not sufficient to result in rainfall.

One of the best indicators of climate change in mountainous areas are glaciers, which integrate all of these effects and serve as a very effective barometer of climate change. According to the European Space Agency, glaciers around the world have lost over nine trillion metric tons of ice since 1961, contributing 27 mm (about an inch) to sea level rise. Below is one example of ice loss from the Vernagt glacier in Austria.

|

| Source: http://www.adabei.info/Gletscher/ |

Studies of mountainous regions indicate strong elevation-dependent and seasonal-dependent effects of climate change on snowfall and snowpack characteristics during the 21st century. For example, the figures below include projected trends from 14 climate models in several snow variables in the European Alps from 1981–2010 to 2070–2099 assuming a high-emissions scenario. The left hand column shows seasonal (September to May) trends as a function of elevation. The dashed line indicates no trend with values to the left indicating percentage declines and values to the right percentage increases. The larger filled triangles are the multi-model mean.

For this high-emissions scenario, mean Sep–May snowfall (i.e., the water equivalent of snowfall) declines are largest at lower elevations (> 80% for the multi model mean) and smallest at upper elevations (< 10% for the multimodel mean). The graphs in the top row to the right show trend by month. The largest trends are during the fall and spring. The smallest are during January and February. In the < 1000 and 1000-2000 m elevation bands, there are declines every month. Above 2000 meters, some models actually generate a slight increase in snowfall from December to March. This may seem paradoxical, but snowfall is dependent on the amount of precipitation and the fraction of that precipitation that falls as snow. These are cold altitudes in the current climate and warming favors an increase in precipitation, most of which will still fall as snow (see the bottom row).

Declines in storm frequency and increases in storm intensity are expected with global warming, and at all elevations snowfall frequency declines. The decline is largest in the lower elevations because snowfall becomes less common as more and more storms produce rain.

Snowfall intensity as calculated for this study is pretty odd because it is the average snowfall intensity (water equivalent per day) on days with snow. In the lowest elevations, this actually goes up because there are few snow days, but when it does snow, it snows like hell.

Heavy snowfall might be a better measure. This is the trend in snowfall on the top 1% of snowfall days. Basically, the biggest events. Those go down at all but the highest elevations. Maximum 1 day snowfall exhibits similar trends. It is worth noting, however, that this is for a high-emissions scenario with a great deal of warming, so many storms are producing rain. For a lower emissions scenario, largest 1 day events in the lower-to-mid elevations might stay about the same or increase some. It's basically a race between storms becoming more intense but temperatures increasing to result in more rain.

So let's summarize. It's getting warmer and warm spells are becoming more frequent and extreme. Storms are trending to be a little less frequent and a little more intense. Impacts on snowfall, snow fraction, and snow frequency are elevation dependent. Trends for these variables in the Alps (and many other midlatitude mountainous areas) are expected to be large and negative in the lower elevations and smallest or possibly even positive in the upper elevations. The size of these trends will depend on future greenhouse gas emissions. The graphs above above assume a high emissions scenario. Under a lower emissions scenario, declines at lower and mid elevations may be much smaller. There could be an increase in the size of the largest snowfall events before the caustic effects of temperature increases result in more and more precipitation falling as rain.

This sets the table for part II when we look at what all this means for snowpack and avalanches.